Pre-Submergence Salvage

Pre-Submergence Salvage

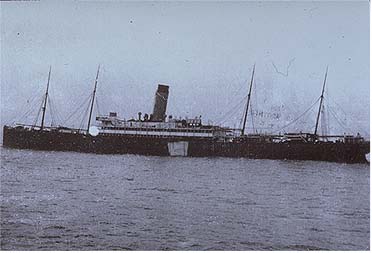

Pre-Submergence SalvageThe REPUBLIC was struck at 5:40 a.m. Saturday, January 23, 1909, on the port side amidships, reducing a half dozen staterooms to rubble. The FLORIDA tore from the upper decks to below the water line and penetrated the REPUBLIC's engine room, also rupturing the bulkhead which separated the boiler room from the engine compartment. Both compartments began to flood. The REPUBLIC's boilers were immediately shut down to prevent explosion which resulted in the loss of all motive and electrical power, excepting the electrical power remaining in her storage batteries for limited use of the wireless telegraph. Although newspaper accounts essentially document only two rescue transfers, three transfers occurred. The transfers can be sequentially identified as follows (See also: Log of the Wreck):

The First Transfer At 7:00 a. m., January 23rd, a first transfer by small boats of passengers from the REPUBLIC - a vessel in some jeopardy and without heat, steam-power or electrical light - to the less critically damaged FLORIDA began.

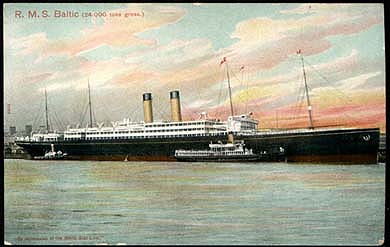

The Republic has a long gangway which is really three flights of stairs having small platforms between, but these stairs are none too steady in the best of weather and with a vessel rolling in the usual swell of the ocean it would be an easy matter to slip into the sea. Moreover, 70 per cent of the passengers were women and they had to be helped down the gangway by sailors, who were stationed at intervals. On the Florida things were not so comfortable and rope ladders were used to board that vessel from the boats. ... N. Y. Sun, January 25, 09, 1:6 Without steam or electrical power to operate her winches - without adequate means of removing five tons of American Gold Eagles from the REPUBLIC and transferring that cargo to the FLORIDA (whose seaworthiness was also in jeopardy) - the REPUBLIC's crew was incapable of transporting anything other than the passengers, in whatever clothes that they had hastily put on, to the FLORIDA. The Second Transfer The first rescue vessel, the White Star Liner BALTIC, arrived at the scene at 6:00 p. m., over twelve hours after the collision, and, by which time, the REPUBLIC had settled close to 40 feet down by her stern. [aboard the FLORIDA] At about six o'clock a strange whistle was heard. Everybody said 'The Baltic,' but rather hoped than believed. But so it was. By and by could be seen her white house-lights. The passengers cheered and crowed the decks to view her. A most beautiful apparition, and the fog lifting and the clear sky opening revealed the big ship with her entire upper works lit up like a gorgeous dance hall. Everybody vowed she was the finest, handsomest, and altogether the most transcendently lovely creation that was ever put in commission. But for all that she did not stay with us. No, she steamed back to the side of the Republic and there remained, looking after her company's property no doubt - all very well at any other time, but here were fifteen hundred souls who could not see why they were not taken off while the sea was smooth, the air dry and the sky alight with encouraging stars. Other steamers hove in sight: one a Standard Oil steamer which offered to lower boats and take off passengers, but she was waved away. And it was not a question of saving the lives of the Republic's salvage crew. They were few in number and had boats floating at the ship's side. They had only to step in and row. At about eleven o'clock the Baltic did come near, the word was passed to get ready to leave, women and children first, but now it was foggy and rainy, and the rising sea not so smooth ... The Sinking of the 'Republic'

BALTIC's Captain J.B. Ranson R. N. R. [Royal [after locating the Republic early in the evening] We first took off the crew of the Republic, for she seemed to be sinking. We then drew alongside the Florida, and it did not take long to determine that it was necessary to remove the passengers, for the Florida was not in condition to be trusted with the lives of all the passengers she had on board. Quotation of Baltic's Capt. Ranson Purser Gino Maraviglia of the Florida stated: [After the first transfer of passengers from the Republic to the Florida]"The Republic's passengers stayed on board the Florida an entire day, until it was decided to transfer everybody except the crew of the Florida to the Baltic. The transfer to the Baltic was effected between midnight Sunday and 5 A. M. Monday." New York Times, Jan 26, 1909, 1:2 The Baltic returned to the Florida after 11 p.m. There are no detailed accounts - at least none that have been found to date - that describe the four and one-half hour period during which the Baltic stood by the Republic. This is the only period of time during the 39 hours between collision and sinking where the actions of White Star Line officers and crew aboard or proximate to the Republic are not just vague, but are actually non-existent. The Republic's Mail Cargo.It was reported, however, that 3,200 sacks of mail which were originally placed on board the Republic for shipment, were off-loaded from the Baltic upon her return to New York. NY Times, Jan. 26, 09, 2:5 Captain Ranson did not state, however, when, why or how the mail had been removed. The New York Sun, another morning newspaper, also reported Capt. Ranson's above statement almost verbatim, Jan. 26, 09, 2:1, but, surprisingly, the Sun's account does not include the last two above quoted sentences. . . . According to the figures furnished to Captain Ranson by the purser there were on board the Baltic from the Republic 228 first class passengers, 211 third class passengers and 244 of the crew. . . . In addition to these . . . [s]he also brought in 3,200 sacks of mail.2 N. Y. Herald, Jan. 26, 09, 4:7, and However, the above quotation could be interpreted that the reference concerns the Baltic's own mail cargo, the mail cargo that the Baltic was transporting from Europe to the United States. This analysis, that the 3,200 mail bag reference concerns the Baltic's own mail cargo, NOT Republic's, appears to be confirmed by the Evening Telegram's report of the same Ranson quotation:

Evening Telegram, January 25, 1909, 3:3 A telegram was found within the records of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Supplies and Accounts, that stated: THE WESTERN UNION TELEGRAPH COMPANY

RECEIVED at NAVY DEPARTMENT NewYork 30 Paymaster Dyer, Bureau of Supplies and Accounts, Navy Dept, Wash DC Republic's mail all recovered Postmaster says she had no Fleet mail Maupin NARA RG 143, File 105669. The lack of punctuation and larger spacing between the words "says" and "she" appear in the original. Without punctuation, where does one sentence end and the next begin? Who, precisely, is saying that the Republic's mail was saved, and that she had no fleet mail? And, speaking posthumously of Captain Sealby, who had died December 4, 1942, his friend Captain Robinson stated: ...and nearly everybody is acquainted with his [Captain Sealby's] gallant action when the REPUBLIC was sunk by the Italian Steamship FLORIDA in 1909. The heroic conduct of Sealby who was in command; the operator, Jack Binns, summoning aid by wireless, using it for the first time at sea for this purpose, are well known. Subsequently, every soul aboard the REPUBLIC was saved as well as all of the mail, and Sealby was the last to leave the ship. ...3 Captain Inman Sealby - Skipper and Friend, by But, precisely what did happen when the Baltic stood by the Republic? Jack Binns, the Republic's Radio Operator, talked about the period when the Baltic first approached and, for some period, stood by.

The Baltic at Hand at Last. Perilous Transfer Successful

BINNS'S STORY OF WIRELESS WORK According to Jack Binns' account, before the Baltic arrived, the Republic's officers and crew "were all busily engaged in standing by the boats," and once the Baltic arrived, the officers and crew were then transferred to the Baltic. He, too, does not mention the mail. Of course, prior to the publication of this article, Jack Binns had submitted it to both Captain Sealby and to White Star Line's Vice President, Mr. Franklin. See: Testimony of John R. Binns made to the US Senate Subcommittee of the Committee of Commerce investigating the Titanic disaster, commenced April 19, 1912, Day 13. The officers and crew were busily engaged in standing by the boats, appears to be an obvious edit.

In his official report "made from mental notes, as official report was not rescued from the sunken ship" (Why weren't Binns' notes from Republic saved? Binns had left the Republic to board the Baltic Saturday night but returned to Republic about 9 a.m. Sunday morning as a member of Republic's salvage crew, and then left her again, finally, about 4 p.m. Sunday to board the Gresham. He certainly had more than enough opportunity to save any important documents.) that he subsequently presented to his employer, the Marconi Company, Jack Binns stated that the Baltic was first visible to him at 8 p.m., which appears to be an attempt to narrow the time frame in which the Baltic stood by the Republic. See: Marconicalling.com. H. J. Tattersall, the Baltic's Marconi Operator, in his Special Report to the Marconi Company, also does not discuss the Republic's mail. Trimming the time during which the Baltic stood by the Republic to slightly over just three hours, from 6:50 p.m. to 10 p.m., he wrote: . . . About 6.50 p.m. the Republic was found with the Florida laying alongside. The fog which had been dense all day was at that time lifting and the two ships were clearly seen. The Republic appeared very low in the water, but was lying on an even keel. We afterwards learnt that for some hours she had been settling at the rate of 1 foot per hour. The Florida had a list to port and had settled down at the bows. No lights were to be seen on the Republic except one mast head light, a tail light and one on the bridge. About 7.30 p.m. the remainder of the Republic's crew came alongside in small boats and were taken aboard. Captain Sealby and the Chief Officer remained alongside the Republic. At 9.00 p.m. we resumed the regular routine of working [with the wireless] which had been suspended at the request of the Republic and commenced sending and receiving traffic from Siasconset. Messages were quickly being handed in by the rescued Passengers and crew and the working with Siasconset became very heavy. Occasional traffic passed between other stations. About 10.00 p.m. [?] we commenced transferring the Passengers and crew from the Florida and for about 8 hours the life boats were continually coming and going, bringing the rescued. At daybreak [? See Footnote 4] we left the Furnessia standing by the Florida, and proceeded back to the Republic when a skeleton crew was again sent on board.4 The Lucania and New York had been standing by the Republic during the night but upon our approach they put about and steamed for New York. After instructing the Furnessia to stand by the two boats we also proceeded to New York. . . . Special Report of the S/S Baltic The Republic's Third Officer Sydenham E. Stubbs' account is particularly vague on this period of time. The BALTIC's signals were now very plain, and she hove in sight at 6 p. m., having been directed to us by wireless. Half-an-hour later we left the REPUBLIC and stood off her in the ship's boats. At 7 p. m. the weather became thicker, with a rising sea and rain. We decided to start transferring all the passengers from the FLORIDA to the BALTIC. This work went on through the night and was carried out under very adverse conditions, being completed at 10 a. m. the next day (Sunday)[sic]. We had thus transferred since the accident a total of 2,494 souls, made up as follows: 297 crew personnel of the REPUBLIC, twice; 525 passengers of the REPUBLIC, twice; and 850 third-class passengers of the FLORIDA. ... Sinking of the REPUBLIC, Sea Breezes Commander Stubbs' account of the incident is extremely detailed, except for the period between approximately 6 p. m. and 11 p. m. when the Baltic stood by the Republic. In fact, his report suggests that the transfer of passengers from the Florida to the Baltic began at 7 p.m.! The removal of Republic's mail would have been a significant event, but neither the Company nor Captain Bayerle have been able to locate any more than just a few sentences, with all but one of the few stating that the mail had been removed, and all without any further elaboration. A week after the collision, the Boston Post reported that only twenty-eight (28) bags of mail had been saved from the Republic. SAVED REPUBLIC'S MAIL Pouches From Wrecked Steamer Boston Post, Jan. 30, 09, 5:3 [Describing the Romanic's Boston departure on January 30, with ten saloon and 49 steerage passengers and 47 crew who had been on the Republic, the article continues ...] Boston Post, Jan. 31, 1909, 6:5 The information concerning the items actually saved from Republic, if anything was saved other than the passengers, crew and a few personal items - appears at best to be deliberately constrained, or, at worst, deliberately deceptive. Perhaps White Star Line did not want to confirm the fact that the Republic had been a mail carrier. It was well known at the time (and today) that mail ships also frequently carried gold cargos. Indeed, a vessel and her Company owners had to meet specified insurance classification and regulatory requirements in order to be legally sanctioned to transport mail, a prerequisite in order to also transport gold. To the extent possible, the Line probably did not want to state what had been saved, and, by implication, what hadn't. Motivation and Mechanism for Mail Removal Mails. Mail bags may be carried by contract or otherwise. Such cargo must be considered as "precious," and great care must be taken to see that it is well stowed in a place where it will receive no damage from wet or vermin, and in a compartment (preferably a "lock up") where there is least risk of any of the packages being pilfered. Mail should be ready to be discharged immediately on arrival so that undue delay in delivery is avoided. Practical Cargo Stowage for Ships' Officers The Edwardian era marked the high point of international Sea Post Service. Most shipping lines relied upon the revenues generated by sea post contracts to survive. [Emphasis supplied.] Sea post clerks were highly skilled and respected postal workers who sorted, canceled and redistributed the mail in transit. Regarded as the best of the best, these men typically sorted over 60,000 letters a day, making few, if any errors in the process. Their hard work and efficiency allowed the mail to be delivered immediately or forwarded directly to other destinations at the end of a voyage. Posted Aboard R.M.S. Titanic, Exhibit,

Typical Ship's Mail Sorting Room A liner's mailroom was kept busy. The mail had to be sorted during the voyage, and, therefore, had to be accessible. Mail had to be accessible, too, to avoid undue delay in offloading. In contrast, for security, gold was deliberately stored to be inaccessible during the transatlantic crossing (see Gold Storage, next). The mail on the Republic was probably kept within the first class baggage room or mail room, both rooms located generally on the middle deck forward of the main deck house.5 This area, forward of the collision area, was high and dry when the Baltic arrived. No doubt, among his other concerns, Captain Sealby was also concerned for the Republic's mail cargo. His concern was most likely influenced not only by the physical location of the mail and its accessibility, but also by the physical and intrinsic differences between mail and gold. Mail, if wet, can be damaged or destroyed. Gold was impervious to such damage. Mail may contain unique and irreplaceable items, and registered mail may contain items of great monetary value. Anecdotal evidence of the consequences of "the letter that never arrived" are well known. Gold of such-and-such a certain value could be replaced. And, also, a method to remove the mail - the standard method of offloading mail via canvas mail chutes - was available. Winches and booms of the Baltic were designed to remove her own cargo from her own holds to dockside. They were not designed to remove cargo from another vessel on the high seas. Mail, however, was normally removed from mailships with the use of canvas chutes to "slide" the mail to awaiting mailboats once the vessel reached Quarantine. This routine procedure, appropriately modified, could have been used to offload Republic's mail to pre-positioned cargo nets within the Republic's already launched lifeboats, and then via them transported to and winched aboard the Baltic.

In less than five hours, all of the Titanic's 3,364 mailbags would have been transferred to harbor boats using canvas chutes like this being used to guide mailbags into the hull of S.S. President, one of the U.S. government's two harbor mail boats in use in 1912. Posted Aboard R.M.S. Titanic, Exhibit, A line of men and small boats could conceivably remove 3,200 bags of mail in 4 1/2 hours, but to move seventy-five 160 pound boxes of gold coin from deep within the hold [see "Gold Storage," next] of a poorly lighted, sinking vessel, down a gangway, into small boats, across a few hundred feet of open ocean and up another gangway or rope ladder - is another matter, for no one knew just how long the Republic might stay afloat. It would have been a labor intensive task even at dockside. [Describing the gold removal on the Lusitania ...] A gang of longshoremen rushed up the freight gangplank and tackled the piles of small wooden boxes. N. Y. Times, November 9, 07, 2:3 Finally, the mail was probably removed (IF it was removed, discussed next) to the Baltic out of greater concern for the maintenance of delivery schedules (and the maintenance of White Star Line's mail contracts) rather than out of fear that the "practically unsinkable" Republic might founder. See: The Practically Unsinkable Republic. ... The wrecking steamer had started to the assistance of the Republic from New York and the tugs Mary F. Scully and Gaspee from Providence. The Republic's wireless operator, Binns, had his apparatus working again for short distances using storage batteries. Before the Baltic turned about for this port the Anchor Liner Furnessia had come up and was standing by the Republic, her captain under orders from his company to furnish any relief that Capt. Sealby asked for. The Furnessia at 4 o'clock yesterday afternoon got [sent] a wireless message here saying that the Republic had asked for a tow and that she had already headed for New York with the Republic on her line. The revenue cutter Gresham was acting as a rudder for the Republic. The boats were headed west at the time the message was received, keeping to shoal water and making about eight miles an hour. The Furnessia, not a mail steamer, could take time for the salvage job. N. Y. Sun, January 25, 09, 2:5 [Describing the 8,000 ton Eqypt's collision in 1922, in fog] It is well known that liners, especially mail-boats, are often obliged to steam fast in fog to keep up on their time-tables, but near Ushant [where the Egypt was lost] exceptional caution is called for and is generally used. The Egypt's Gold, David Scott, Penguin Books, 1939, p. 268. But Was the Mail Really Removed? The lack of information concerning the mail's removal leads to additional speculation. Why did Binns, Tattersall and Stubbs not mention this at all? Why did Ranson not elaborate? Why can't more than just a few sentences be found that concern the mail's removal - out of the voluminous news-coverage of this historic event? Certainly, the postal service would have had a report on the issue in the manner of the postal service's 1912 discussion of the loss of mail aboard Titanic, but no similar report, or even mention, can be found within 1909 postal reports. CLOSING OF MAILS AT NEW YORK European Mails. ...

New York Herald, Jan. 21, 09, 14:2, The Republic was the only mail carrier departing New York for Europe on January 22, 1909. Could it be that the mail was NOT removed, but because the Republic was KNOWN to have been carrying mail when she departed New York (in the same manner that she was KNOWN to have been carrying Navy provisions - by pre-sailing, pre-collision newspaper accounts), that this potential salvage target also had to be "officially removed" to avoid attention (see the various topics under Concealment. A legally prescribed postal service inquiry also would have been circumvented if the mail had been "saved.")? Speculation on the reason for the Baltic's delay in removing the Florida's human cargo existed even among the passengers. General Brayton Ives, a Republic passenger who had been transferred to the Florida, stated:

Evening World, January 25, 1909, 5:6 An unidentified Republic passenger who reportedly occupied "stateroom 1" and was a prominent Boston resident said,

Boston Journal, January 27, 1909, 2:1. James B. Connolly, another Republic passenger and journalist who was prolific in his reporting of the story and who had been transferred to the Baltic was unaware that the four hour rescue delay may have been attributable to the removal of mail from the Republic. On January 25, 1909, he wrote:

Evening World, January 25, 1909, 4:7 and, on January 26, 1909, Connolly asked: I would like to know why it was the steamer Baltic paid so much attention to the Steamer Republic after the passengers had been transferred, while the steamer Florida was standing a short distance away, for all they knew in danger of sinking with passengers on board. ...1 Nor has any mention of the Republic's mail been found among the accounts given by the Baltic's own passengers, or anyone else. I don't believe that anyone would have seen the mail's removal as an insignificant event - the saving of the registered mail alone would have saved potentially large sums of money. So why not advertise the fact, expound upon it, give credit to the seamen who accomplished that feat? A contrary result - the loss of mail - is mentioned in a letter (file copy) dated December 2, 1910, from (signature illegible6) Pay Inspector, U.S.N, General Storekeeper to Henry A. Wise, U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York; the letter concerns the Bills of Lading which were used for the U.S. Government's shipments aboard Republic. The bills of lading were signed by the company and received by a representative of this department on delivery of the freight to the S.S.REPUBLIC. The original bill of lading was mailed to the Commanding Officer of the CULGOA, and was no doubt lost with the mail aboard the REPUBLIC. [Emphasis supplied.] NARA RG 80, File 26835-15. White Star Line may have desired to be deliberately vague on what may have transpired during this four-hour gap in the rescue record. To leave unanswered the question, "What was removed, if anything, when the Baltic stood by the Republic?," would assist in the concealment of any lost cargos. However, under normal circumstances, if 3,200 bags of mail were removed, it would have taken over four hours to complete that task alone - which would have left insufficient time to remove the gold - even if the gold had been accessible ... Explanation for the Delay One reason for the delay in the transfer of passengers from the Florida to the Baltic was, in fact, the very change in weather conditions that, according to this report, then placed the Florida in potential jeopardy. Baltic Decides Time to Act New York American, January 25, 1909, 1:6 But, still, what the Baltic did during this interval is not described in detail. Captain Ranson was certainly communicating with the various participants, holding discussions with them, and developing contingency plans. Given the dense fog, the number of ships in the vicinity, the delayed relayed communications with shore-side White Star line officials, and the monitoring of changing weather conditions - the use of three to four hours in developing and implementing a plan cannot be seen as an idle or unreasonable use of time. However, it is interesting to note that, for a considerable period of time after the loss of Republic, newspaper accounts did not report any further gold shipments (when exports took place) aboard other White Star liners. The remaining seven gold shipments to Europe for 1909 were reportedly shipped aboard American Line, French Line and North German Lloyd ships. The last gold shipment aboard a White Star Line vessel for 1909 was the shipment reportedly sent on January 13, 1909, aboard the Oceanic. See: The Oceanic's Cargo. |

|||

FOOTNOTES1On January 26, 1909, Connolly was unsure as to the cause for the delay. He stated to the Boston Post: "I would like to know why it was the steamer Baltic paid so much attention to the Steamer Republic after the passengers had been transferred, while the steamer Florida was standing a short distance away, for all they knew in danger of sinking with passengers on board." Boston Post, Jan. 26, 09, 3:3. 2The NY Times reported that there were "no second cabin" passengers, NY Times, Jan. 24, 2:5 and 4:1. The Second Class areas of Republic, where we believe the gold was most likely stored [See: Gold Storage, next] were, apparently, unoccupied and may have been under charter. 3If the Republic had carried gold and if the gold had been removed, one would think that, since he is eulogizing Captain Sealby over thirty-three years after the Republic's loss, Captain Robinson would have also included this result. 4Tattersall's times are inconsistent. On January 24, 1909, apparent sunrise at the wrecksite occurred at 6:56 a.m. (See: NOAA Sunrise/Sunset Calculator) But Tattersall states in another internal Marconi report: "About 9.30 a.m. small crew and wireless operator were sent back on board the Republic." Extract from the Report of the S/S "Baltic," Saturday January 23rd contd., H. J. Tattersall, Marconi Archives. 5Titanic's Postal Department was forward below her waterline on G-Deck Starboard side which was one of the first areas to flood in that collision. Titanic's Sorting Room was on G-Deck and the Mail Room on the Orlop-Deck as on the the 'Olympic.' Within 5 minutes of her collision the water was up to the Postal Clerk's knees and they dragged the wet mail bags up steep stairways to the starboard side corridor of D-Deck's forward cabins. They had enlisted the aid of any stewards available hoping to off-load the mail thorough Titanic's First-Class entrance. The Titanic sank headfirst. It is estimated that between 3,364 and 3,435 bags of mail, 200 of which were registered mailbags containing 1.6 million pieces of registered mail, and between 700 and 800 parcel post shipments were lost in the sinking. See: Titanic's Mail, James H. Bruns, EnRoute, Volumn 1 Issue 1, January-March 1992, Smithsonian National Postal Museum, available on-line at: http://www.si.edu/postal/membership/newsv1issue1.html. The Smithsonian's Exhibition Posted Aboard R.M.S. Titanic is available on-line at: http://www.si.edu/postal/titanic/titanic.html. 6This letter was probably written by Reah Frazer, Pay Director, U.S.N., General Storekeeper, United States Navy Yard, New York. Reah Frazer had signed the Government's Bills of Lading in regard to the Government shipments on-board Republic. See Footnote 3 at: The U.S. Government's Cargos - An Accounting. |

|||