Gold Storageand Why The Gold Could Not Have Been Removed During The Second Transfer If a vessel was equipped with a designated "treasure chamber" or security lockers, these storage areas would generally be located in the lower decks. With almost as little ceremony as though it had been a consignment of pig iron, the $12,361,150 in gold which arrived yesterday on the Cunard Liner Lusitania was removed from the steel-lined room on the lower deck and hustled out to the pier. N. Y. Times, November 9, 07, 2:3

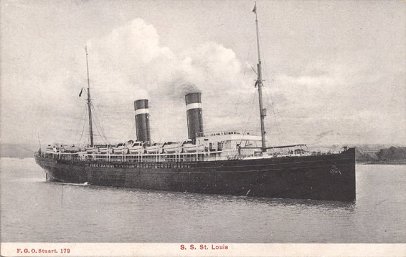

USMS (United States Mail Ship) St. Louis, 554 feet, 11,626 tons Baggage The stowage of baggage, marked "Not Wanted On Voyage" is a special duty and generally devolves upon the supervision of one of the officers who is designated "baggage officer," and has general charge of the baggage hold or trunk. In the S.S. St. Louis, during her prime as a passenger carrier, this duty fell to the Senior Second Officer, and such baggage was stowed in a deep trunk hatch filling up the space above the specie room. To get at the treasure it was first necessary to hoist out a thousand trunks or so. A special king post was available for hoisting this baggage out quickly and on approaching port, in fine weather, the greater part of it was got up on deck before coming alongside. It was then slid down on the dock for customs inspection on long skids. ... Specie Most first-class vessels have a specie room and from time to time transport great quantities of gold and silver. This is specially so of vessels in the Transatlantic Trade. The specie room is a strong box located near the bottom of the vessel. A good plan is to locate this room at the bottom of a trunk hatch, and after the specie is on board fill the hatch with the baggage not wanted on voyage. This makes it impossible to get at the treasure without hoisting out the entire cargo of baggage. In slinging specie use a wire net, and have a stout treasure net suspended under the gangway. Silver comes in pigs and is usually slid down wooden skids. Gold is generally carried in kegs [gold bars] and should be slung in nets. The ship's Purser usually signs for the specie himself. The Master, however, is directly responsible and where specie is carried should satisfy himself that all necessary precautions are being taken. Felix Riesenberg, Standard Seamanship for The 8,000-ton P. & O. liner RMS Egypt carried approximately $5 million in gold and silver when she was lost, also as a result of a collision in fog, in 1922. Her cargo was successfully salvaged over a period of nine on-site months during the years 1931 and 1932. Pertinent remarks as to the location of her bullion room follow. ...The boat-deck consisted only of iron beams covered with wooden planking, and a good deal of the planking was already torn up or rotted. The three other decks below, which would have to be pierced before the bullion-room was reached, were much stronger than this. The hurricane deck and upper deck were of iron and the main deck of steel, the first two 8mm. and the last 11 mm. thick. The Egypt's Gold, David Scott, Penguin Books, 1939, p. 93-4. [T] here was a burning question to be put to the designers of the Egypt and of liners in general. Why on earth should a liner's bullion-room be buried in the depths of her hull, under half a dozen decks? Is this imitation of a treasure-vault merely copied by force of habit from the banks on land? The greatest risk to bullion carried at sea is surely that of loss by the sinking of the ship, not by theft. Yet the bullion is solemnly stowed in the part of the ship where theft is easiest - since the lower 'tween-decks are deserted and unwatched most of the time - and where salvage, if the ship sinks, is most difficult. ... Ibid., p. 216. Not only was a ship's bullion room most commonly placed in the lower decks, but security was also considered in the actual loading of the bullion room itself. The officer in charge of the bullion-room would naturally try to protect the gold and silver in every way. If it were alone in the bullion-room, a man with a false key - you never know whom you may have among the crew of a big ship, some enlisted at the last moment - might very quickly get into the bullion-room, burst open a box of sovereigns, take as many as he could carry and escape unobserved. But if the bullion [within the bullion-room] were covered with miscellaneous cargo, the thief would have to pull out a lot of bulky stuff before he could get at the sovereigns, and his chances of success would be much less. Ibid., p. 230-1. Another possibility exists that the $3,000,000 American Gold Eagle engagement was stored in the second class baggage room, as might have been the policy of the White Star Line. This could be the reason why the second cabin of Republic was, for her January 22nd 1909 departure, unoccupied.

Practical Cargo Stowage for Ships' Officers The 14,892-ton RMS Laurentic, like the Republic, was laid down at Harland and Wolff, Belfast for the Dominion Line. The Laurentic was to be Dominion Line's Alberta. She was transferred to White Star during construction and was launched in 1908 as Laurentic. When World War I began, Laurentic was immediately commissioned as a troop transport for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. After conversion to armed merchant cruiser service in 1915, she sank off the northern coast of Ireland on 25 January 1917, less than an hour after striking two mines. Laurentic's sinking accounted for the largest loss of life ever in a mining: only 121 of the 475 aboard survived. But, in addition to her passengers and crew, the ship was carrying 3,211 bars of gold worth then approximately £5 million ($25 million). [Discussing the gold salvage of the White Star Liner LAURENTIC] By the middle of December, 1916, the British Treasury was preparing to send £5,000,000 in gold across the Atlantic. The United States had not then declared war on Germany. But American as well as Canadian factories were working twenty-four hours a day to make munitions for Great Britain and her Allies, and those munitions had to be paid for. So in January, 1917, the gold was sent to Liverpool, where it was loaded into the second-class baggage room of the LAURENTIC. ... Shipping Wonders of the World, Vol. 1,

RMS Laurentic, 15,000 tons, 565 Feet long, 67½ foot beam Soon after that a U-boat deposited a mine off Malin Head, Doengal, which made one of the luckiest contacts of the war - the White Star Liner LAURENTIC. She was bound from Liverpool to Halifax without passengers. After the explosion the big ship sank quickly in the bitter January Atlantic, and 354 of the crew died of exposure in the boats. It was a heavy score for a dumb mine, but the ship building struggle would make it up and more men would come forth to sail the ships. It was only a passing incident to Damant, rushing here and there on salvages and demolition. It was not, however, a light matter in Whitehall, Damant was called to London, were several admirals received him in solemn atmosphere. The Director of Naval Ordinance impressed on him the high secrecy of the facts they were about to tell him. The enemy did not know his mine had taken the LAURENTIC, and more certainly did not know what had been sunk in her. Very few persons in England knew and Lieutenant Commander Damant was about to become one of this select group. The LAURENTIC carried in her second-class baggage room five million pounds in gold bars. Laurentic Gold by James Dugan, Captain Minesweepers soon located the wreck. They found the hulk not far [just 2 miles] off the mouth of Lough Swilly in a depth of [126 to]132 feet of water, or 22 fathoms, and buoyed the spot for Damant. ... Men Under the Sea, by Commander The technology to recover gold bars from a wreck in 132 feet of water, only 2 miles from shore, existed. Royal Navy divers made some 5,000 dives to the wreck over nine years between 1917 and 1924. At a cost of only £128,000 ($640,000), they succeeded in recovering all but 25 of the bars. The Royal Navy returned to the site in 1952 to recover the remainder, reportedly salvaging all but six bars. In the familiar fashion of layout of most liners of the day, the second class area was aft of the funnel. The second-class baggage room of the REPUBLIC would be below decks and within 40 feet aft of the collision area, one of the areas which flooded rapidly; the REPUBLIC sank stern first. If the REPUBLIC's gold was carried in the below decks second-class baggage room, specie room, or security lockers, where gold would normally be stored, the gold was probably submerged soon after the collision. Should the gold not have been carried in the usual location, it, nevertheless, would have been virtually impossible to conduct a high-seas transfer of the gold - stored probably beneath several thousand trunks or tons of other cargo - to the BALTIC without any mechanical assistance or with, at most, the use of manpower, gangways and small boats. With the primary objective of saving passengers' lives, time alone would have precluded any possibility of saving a gold cargo. Another important consideration is that 29 hours after the collision, the White Star Line and Captain Sealby were making arrangements to tow the REPUBLIC into repair facilities; they were under the informed impression that the REPUBLIC was "certain[ly] in no immediate danger of sinking" and that her condition was "favorable for salvage." Therefore, even if the gold room was accessible, there was no perceived absolute necessity to risk a high-seas transfer.1 It was not until "before six o'clock on Sunday night," just slightly more than two hours before the REPUBLIC settled to the bottom, that Captain Sealby knew with certainty "that the Republic would never live to reach Martha's Vineyard." The quotation continues: By seven o'clock she was way down in the stern and wallowing with long, painful rolls that meant there was very little more life left in her. Williams (R. J. Williams, the second officer) and I stood on the bridge and kept our eyes ahead on the lights of the Gresham and Seneca, which were towing. The ship was so low in the stern that the waves were breaking over her at that point, and the water was swashing clear up to the ladder of the saloon deck aft. 'I think it must have been just about eight o'clock when we both saw that she was going to drop under us within a very few minutes. ...' How Captain Sealby Stood by His Ship, It would have been impossible to remove any cargo while the REPUBLIC was under tow. And when it was certain that the REPUBLIC would sink, the areas which presumably contained the gold cargo, if not submerged soon after the collision, by that time would have certainly been submerged. Furthermore, if the gold had been taken off prior to the REPUBLIC's sinking, it would have been reshipped and would be reflected as received in our export/import study. The conclusions of our study substantiate only a loss of the specific January 12th engagement of $3,000,000 in American Gold Eagles. In the final analysis, Captain Sealby's actions were in accord with insurance underwriters' suggestions to Masters of vessels: 1. to assure the safety of his passengers; and 2. because the Republic was expected to remain afloat, to leave her cargo in place.

THE CARGO. 5th. In no case ought the cargo to be unladen without the clearest necessity. [Emphasis supplied.] It is not only very expensive, but creates great delay, and is apt to end in serious injury to the cargo. The intelligent shipmaster will generally form a good opinion on this subject, and should consult such skillful persons as he may find, and who can gain nothing by his unloading. ... Suggestions to Masters of Vessels The Third Transfer The BALTIC returned to the FLORIDA at 11:00 p.m. and commenced a third transfer of the combined REPUBLIC and FLORIDA passengers from the FLORIDA to the BALTIC, again by small boats. It was 11:40 o'clock on Saturday night when the work of transferring the passengers began. ... The first boat in charge of the first officer pulled alongside the Florida and while sailors held her steady in position under the ladder the passengers, women first, were helped down... N. Y. Sun, January 25, 09, 2:4 One of the passengers said: 'Our lifeboat was heavily laden, and for more than three-quarters of an hour we pitched and rolled in that sea trying to get to the gangway of the Baltic. We were only half dressed, and the drenching rain soaked us to the skin. When we got near to the Baltic we saw that our boat was much lower than the accommodation ladder reached. Two seamen at the foot of the ladder lifted my sister from her seat in the boat and tried to get her on to the ladder, but as the boat swung away she lost her balance and fell into the water. Twice she sank before the seamen could catch her dress with a boat-hook. Holding her with a boat-hook they caught her first by her hair and then under the arms, and dragged her forth to safety. We had only the clothes we had on, and we had lost all our money, jewellery, and baggage.' Liverpool Courier, January 26, 09, 7:6 | |

FOOTNOTES1The impression that the REPUBLIC would remain afloat is discussed in The Practically Unsinkable Republic, and Other Cargos, Passenger Effects. | |

| . . | |